“Pieta” by Michelangelo, housed in St. Peter’s Basilica

“Pieta” by Michelangelo, housed in St. Peter’s Basilica

The scope of Michelangelo’s world is beautifully staggering. Here is the second post (part one is located here.) on some of the numerous lessons we can gleam from the life of this artist.

Michelangelo Lesson: Always Continue your Art Education

Michelangelo Lesson: Learn from the Greats

“I am still learning.” — Michelangelo

“I regret ….that I am dying just as I am beginning to learn the alphabet of my profession.”

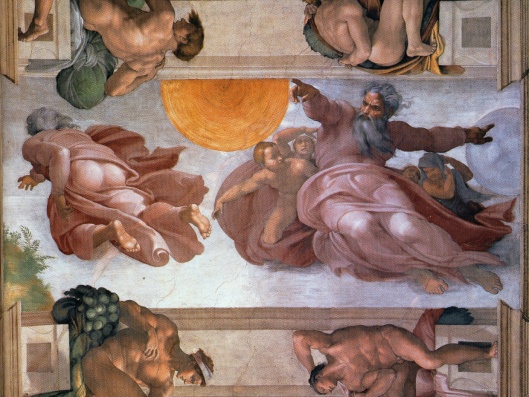

When Michelangelo accepted the commission of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, he knew he would have to learn many new skills. He thought he would have to master painting (which he abandoned as a teenager, when he discovered sculpture.) He would have to learn the technique of “buon fresco” (which was difficult enough, but he knew he would have to develop methods for fresco arching overhead.) And he would to specialize in curvilinear perspective, for the vault was curved and the viewer would be 65 feet below and looking up (which is why some of the figures in conventional photography look distortional.)

Michelangelo was a great admirer of the classical sculpture of the ancient Greeks and Romans. It is said that he personally witnessed the excavation of the statue ‘The Lacoön.” The combination of the sensuous forms in this sculpture plus its mountmental scale are said to have influenced both his sculptural compositions and the entwining of humans forms in the Sistine Chapel.

Although the study of human anatomy could bring torture and even death, Michelangelo was know to be a skilled anatomist. He considered the study of this forbidden subject to be fundamental to the structure of his work.

One of the wonders of art-making is that there is always more to learn, that the journey of creativity never ends. We artists no longer risk death in furthering our artistic education — so take a class, sign up for a workshop, or purchase a book on a new techniques that fascinates your imagination.You might wish to make a great artist, living or of the past, your mentor — or you might immerse yourself in an specific era of art history to apprentice yourself to lessons their example might impart to you. We need to develop and maintain the spirit of experimentation and exploration in the scope of our work.

The “David” — iconic work of Michelangelo

Michelangelo Lesson: Use Lavish Materials Lavishly

Michelangelo Lesson: Use the Materials You Have

“The more the marbles wastes, the more the statue grows.”

The above quote derives from criticism that he was wasting stone in his method of sculpting.

Michelangelo was know to travel great distances to supervise the quarrying of his marble and to attend to special transportation so that his materials were not damaged during long journeys on rutted roads by donkey cart. He also meticulous care in the preparation of paint for the Sistine Chapel.

But Michelangelo also took over the tall marble (over 11 feet) for the “David” which was originally started by another artist plus there was a flaw in the stone that was thought to be impossible to overcome.

The only waste of paint is when it remains snugly in the tube, for it is a cause and effect function that the more paint one places on the palette — the more one will paint.

Although many artists take into account the duration of time they might wish for their works of art to endure, and purchase the best quality of materials, few think as far in the future as Michelangelo, whose Sistine Chapel just celebrated 500 years. Nevertheless, it is ideal to have the best possible opportunity for survival under current circumstances.

Some artists have no care for any conservation of their work. I knew one artist who in effect wrote on the back of a painting something in the order of ”let it rot” to any future conservators — viewing changes and decay as part of the creation process.. But each artist must measure the quality of their raw materials and their philosophy of longevity of their work.

“Sybil” — drawing for the Sistine Chapel

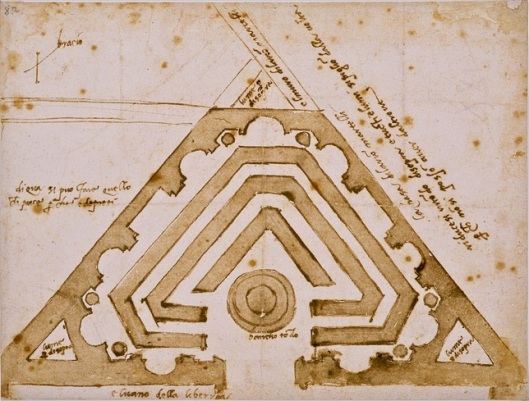

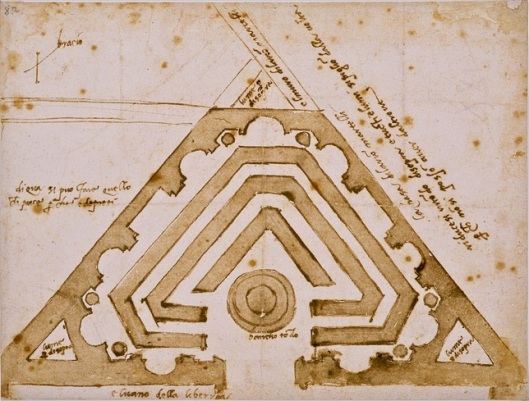

Michelangelo’s shopping list and drawings for the Sistine Chapel

Michelangelo Lesson: Draw More —

“Design, which by another name is called drawing . . . is the fount and body of painting and sculpture and architecture and of every other kind of painting and the root of all sciences.”

“Let whoever may have attained to so much as to have the power of drawing know that he holds a great treasure.”

“Draw…, draw – draw and don’t waste time!”

“Believe it or not, I can actually draw.”

Drawing in the Renaissance of Florence and Rome was considered the prime source of visual virtuosity, the main source of exploration into nature and essential for the advancement of knowledge. During that period, drawing was considered the first step in painting and in other works of art and science.

Michelangelo was a compulsive drawer. He was enamored with the process of drawing. It was not until he was in his 50’s that he produced what he considered finished drawings (which makes all the “Presentation Drawings” — included in Part 1 — given for educational and emotional reasons, all the more remarkable.)

In Michelangelo’s drawings one notices his use of the paper. Variations on a theme often crowds every inch of the page. One receives the impression that perhaps he was so engrossed in the process of drawing, following the fleeting shadow of vision, that he did not wish to stop to find another sheet. Or perhaps he simply wished to make efficient and prudent use of his supplies, for his drawings were mainly considered personal and private and were jealously guarded.

Now days, drawing has fallen by the wayside as an important endeavor. But we are also freed to have drawing as a separate art form, as many artists paint directly on the surface without the intermediary step of drawing. And we are no longer tethered to representation but can roam into the realm of personal sensation and vision.

Michelangelo plan for a secret library

Michelangelo Lesson: Muster and Master Time

“There is no greater harm than that of time wasted.”

“Genius is eternal patience.”

Michelangelo was sensitive to the amount of time given in one’s life. Problems with time management and procrastination are not unique to artists, but perhaps we artists experience these dilemmas of the passage of moments more acutely.

There is a season in the creative process — particularly upon completion of a major project or endeavor, when we need to lie quiet as a fallow field in renewal and replenishment, Some artists also refer to this phenomena as “filling the well (of creation.)”

But at other periods — there is the incursion of the duties of daily life that intrude upon time needed for our studio practice. There is also the mirage termed as “artist’s block” when artists maintain they are simply incapable of creative work because of the lack of inspiration.

We artists need to distinguish between these various manifestations of problems with time management. We need to honor fallow periods as a phase of the creative process, while simultaneously, even subconsciously, begin the naissance of our next work. And the demands of the everyday will always expand to flood and chock every minute of our lives. For that aspect, we need to schedule studio time and keep that appointment sacred for our creativity.

For those who feel “blocked” and bereft of inspiration — remove that word from your artistic vocabulary. The universe is resplendent with creative energy. Start on anything, anywhere, play-mess-around-doodle — do something for a specific period of time, even if it is only for 15 minutes. At some point, usually very quickly, you will feel the creative fire to continue and the brush of the wings of your angel of inspiration.

“Piazza del Campidogilo” — designed by Michelangelo

Michelangelo Lesson: Develop a Unique Approach and Perspective

“I dare affirm that any artist… who has nothing singular, eccentric, or at least reputed to be so, in his person, will never become a superior talent.”

“Already at 16, my mind was a battlefield: my love of pagan beauty, the male nude, at war with my religious faith. A polarity of themes and forms – one spiritual, the other earthly.”

Michelangelo seemed to always have a personal twist in his work. He was commissioned to have only 12 figures for the Sistine ceiling — but he composed a suite of over 300 figures plus the tromp-oeil of architectural details.

With the “David,” he did not represent the traditional triumphant warrior David after the battle, but the shepherd boy before the fight with a giant, with the assertion of determination in his gaze along with a subtle hint of hidden doubt.

Have a vision of the scope of your potential — explore your contradictions. It is not merely a case of finding one’s unique style but includes an expression of the mysteries of creation and dreams.

The “Slave” or “Prisoners” statues

“The Dying Slave”

My journey with the richness of Michelangelo has expanded the scope of my vision — and also my inquiry into the “Lessons from Michelangelo” which will grow into a third posting to come.

I invite everyone to add their own personal lesson that might be distilled from the work and life of this iconic artist.

Karina Nishi Marcus

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

“Trojan Horse”, 2’X2′ acrylic on canvas, by Suzanne Edminster and I

“Trojan Horse”, 2’X2′ acrylic on canvas, by Suzanne Edminster and I